The diverse and resolute Polish Jewish Community after WWI

We owe our existence to those who came before us.

First, let’s first review some background of Jews in Poland.

Poland converted to Christianity from Paganism quite late in the year 900. The country became a kingdom from a dukedom in the 13th century. In the 14th century one of Europe's first universities opened in Krakow. Polish Renaissance followed; i.e., art, architecture, astronomy (Copernicus).

In Western Europe, in the 13th - 16th centuries, Jews faced persecutions and expulsions for their religion. They were expelled from England in the 13th century. This continued for the rest of the Middle Ages. Jews were exiled from France in the 12th and 13th centuries; eventually they were allowed back. Jews were expelled from Germany during the Black Death, 1346–53, ending in a slaughter of German Jews. The 350 pogroms exterminated most of the German Jewish communities. They were blamed for Black Death, the bubonic plague, that was spread by rats brought by trading ships from Asia. Maltreatment is what made Jews move East. They arrived in Poland slowly over the next 200 years. In the 14th century, they came to Poland by king’s Kazimierz the Great invitation. He believed that their experiences as traders and travelers would help the kingdom grow economically. In return, the king gave the Jews personal protection; they were allowed to practice their religion. Poland was a feudal society. The Nobility owned the land and held power. The serfs lived on and worked the land, but did not own land, they were property tied to the land. Jews, like the serfs could not own land. They were restricted to what jobs they could do. To help grow the economy, Jews served the nobility. They managed the vast estates, collected taxes and handled all transactions. Those jobs entangled them in the management of money.

The church, directed from Rome, was always anti-Jews. It feared that a prosperous non-Christian minority would interfere with the church’s growth and power. Blood Libels started in Western Europe and followed Jews as they moved East. Jews were accused of killing Christ, use blood of Christian children to make matzah. Jews eat matzah on Passover to celebrate the escape from Egypt and slavery. Matzah is an unleavened bread eaten during the seven-day Passover festival to commemorate leaving Egypt in a hurry. Blood Libels disappeared from Western Europe, but not in Eastern Europe, and not under communism. They continue to this day and are prevalent in the Islamic World. Brought there by both, the Nazis and Communists, to turn the Arab world against western ideas and democracies.

During the 18th century, from 1772, Poland "officially" stopped existing for the next 123 years. Russia, Prussia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire divided up Poland until the end of WWI. Poland’s demise really happened from within. The Nobility sold-out their country to their wealthy foreign neighbors for the promise of more land. The Nobility cared only about being land rich. The enemy within did not care who was in control, for them being land rich meant power.

Józef Piłsudski, as the head of state and leader of all Polish troops, represented Poland at the Versailles Treaty. His army successfully defended Poland against the Russian Red Army in the Russo-Polish War of 1919–1920. The Red Army advanced as far as Warsaw. Known as "The Miracle on the Vistula River," the heavily outnumbered Polish troops stopped the enemy. In March 1921, Poland and Russia signed the Treaty of Riga, marking the end to aggressions. This treaty granted Poland large parts of Lithuania, Western Belarus, and Ukraine. Now 1/3 of Polish citizens were minorities. Over a million Jews lived in the East - Lithuania, Ukraine, Belorussia, and as a result 3.3 million Jews became Polish citizens. In Tzarists Russia Jews were mandated to live in the Pale of Settlement: western-Russia, eastern-Poland.

After WWI and again after WWII, Europe’s borders changed drastically. Millions of people were moved east and west. This resettlement of people was never questioned, none were ever designated as refugees. Versailles Treaty at the end of WWI broke up the Empires. After the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Europe’s borders were rearranged. This rearrangement of borders occurred again after WWII. After WWI, the Ottoman Empire was also dismantled and the borders were rearranged; this is how the Middle East was created. Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Turkey and Saudi Arabia did not exist, all were made up after WWI. Their right to self-determination is never questioned. Israel was supposed to be reestablished after WWI. The Balfour Declaration by the British in 1917 supported the reestablishment of a "national political homeland of the Jewish people in Palestine”. The Romans renamed Judea to Syria-Palestina, ln Latin, the land of the Philistines, to distance Jews from their homeland. Arab violence prevented the reestablishment of the only Jewish homeland. The British and French took control of this region in 1917 through1948. Under the British Mandate Jews and Arabs became the Palestinians from the Mediterranean to the Iraqi border. Jews wanted to live in Peace, yet Arabs did not. Already in the early 1920s, the Mufti of Jerusalem, Al-Husseini, was inciting Pogroms on the native Jews. He energized Arabs to use violence, invoking that “Palestine is their land and Jews are their dogs”. He called for the killing of Jews: “Kill the Jews - there is no penalty for killing Jews.” The Jewish section of the old city in Jerusalem was under siege by the Arab mobs. Husseini embraced Nazism in the 1930’s and went on to became Hitler’s propaganda minister for the Middle East. He volunteered Muslims for the Waffen-SS and spread Hitler’s propaganda to the Middle East. The Arabs revolted against the Jews. In order to appease them, the British White Papers of 1939 were imposed. Strict quotas on Jewish immigration to Palestine were established during the most horrific period of history, Nazism. They were never removed at any time during WWII.

A historical catastrophe, the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans is what caused centuries of Jews being born in the diaspora. In the late 19th and early 20th century European and Polish Jews became diverse. Besides Orthodoxy, they embraced Bundism and Zionism. Zionists believed that to preserve their identity, heritage, traditions, culture and to live as liberated/self-determined people they had to go back to their native land, the land of their forebearers. Around 5% of Polish Jews made their way to Palestine after WWI and until WWII. Bundists mistakenly believed they could coexist with non-Jews and were safe in Europe. Most Polish Jews were Bundists.

Piłsudski remained in charge of the Polish army until 1923. Troubled by the futility of the Polish government and the wide-spread corruption, he returned to power by waging a successful military coup after a three-year retirement. In 1926, Piłsudski ensured that the Left-wing liberal Sanacja regime remained in power. The National Assembly elected Ignacy Moscicki who became the president of Poland until September 1939. But it was Piłsudski who had the power for the next nine years. Piłsudski's aim was to restore the Polish nation back to a path of moral principles. His government, military in character, mixed democratic and dictatorial elements as it worked to develop a new Polish constitution. His government allowed a multi-party system and his main opposition was the Right-wing, National Democratic Party. The opposition grew radically more Antisemitic as the economic depression of the 1930s worsened. They blamed Poland’s Jewish population for the economic crisis.

America and allies established soup kitchens to feed the hungry and impoverished Polish people as the country slowly recovered from World War I. America also helped to open orphanages. Many children who weren't orphans lived there because their parents couldn't care for them. My grandmother never considered sending any of her six children to an orphanage. Bina Symengauz, came from a poor, religious family. Her mother had stayed home and raised eight children. Grandmother would likewise take on the difficult job of raising her children. But her circumstances become dire before the end of WWI when her thirty-six-year-old husband died suddenly from a simple ear infection. Her husband, my grandfather, Pinkus Talasowicz, came from an observant family of nine siblings. His father, Gerson Talasowicz, was a well-known rabbi and teacher in Warsaw’s Jewish community. He ran a private Jewish school, a “cheder”. Known for his strict discipline, he was feared by his students. He wore traditional black clothes and always walked with a fashionable walking stick. My mother often saw people bow to her grandfather and stop him in the street to ask for advice. After the death of my grandfather, his parents severed all connections to my grandmother, my mother and her siblings. They became strangers to them. The grandparents lived on Stawki Street, across the street from where my mother lived. The large property was surrounded by a fence, the gate was almost always locked. To the side, stood a small house, here the school (cheder) was located. The grandparents lived here with their one unmarried daughter. None of the other siblings followed their father’s orthodoxy. After my grandfather’s death, his side of the family ceased to exist, this act of rejection forever became a source of sadness for my mother.

After WWII, while in Poland, my mother talked about her uncle who lived in America. He was my grandfather's youngest brother. Ludwig Talasiewicz, the youngest son of Gershon and Shoshana. He left Poland on his own when he was a young boy and arrived in New York on January 14, 1914 from London on the steamship St. Louis. Under the name of Louis Tolosewitz, he enlisted in the American army. He fought in World War II when he received a head wound. He was among half a million Jewish Americans who fought Nazism in Europe.

I don’t know the details, but he was injured on the battle field and spent the rest of his life in a Veteran's Hospital in Northport, Long Island. As a child, I had always been intrigued by my mother's tales about her uncle. I always wished for us to meet. He was the first in our family to immigrate to America and he was a war hero. My mother’s sister Paula came to America in 1951. She lingered in a DP camp in Germany for five years after the war. She was able to find their uncle and over the years she kept us informed about his well-being. My wish of meeting him almost came true, but he died only a few years before we came to New York. All connections to Ludwig Talasiewicz vanished with Pola's and my mother's death. I wrote to the Veteran's Hospital on Long Island to try to get information about my hero, great uncle, Louis Tolosewitz, but I did not get a reply.

My grandmother, Bina Symengauz, my mother’s mother, had eight siblings; two of them escaped abroad. One sister with her husband and seven children went to Russia after WWI. Those seven cousins helped my mother and her two siblings survive for two years in Russia, until they disappeared when Hitler attacked Moscow. One brother escaped to Paris. I heard stories about Dovid, one of grandmother’s brothers. Dovid was politically active at the time when Poland was recovering from WWI. He was disturbed by the ineffectiveness of the Polish government. The police discovered Dovid hiding guns in his mother's stove in the summer time, when it was not in use. As a result, Dovid had to go into hiding. His family dressed him as a woman and arranged for false documents to get him out of Poland. Paris became his new home. His best friend also had to leave Poland. He too, was a wanted man. He was married to Estera, the youngest of grandmother’s sisters. After Dovid and his best friend escaped to France, Estera and her baby joined them in Paris. However, Estera missed her siblings and life in Warsaw and after a few years she came back. Her son Itzak grew up with my mother and became like a brother to her.

Dovid sent photographs from Paris of himself and his wife; they had no children. It was only after my mother’s death that I learned the true story of “Dovid”. Bina’s brother real name was Herich Simenhaus. He was born in Warsaw 15/05/1887 to Berek and Sury nee Skrzynia and escaped Poland after WWI to Paris. There, he married a French woman, whose first name was Sara. They lived at 221, rue Jean Jaurès at Bobigny (Seine-Saint-Denis). He was imprisoned by the French Police at the Drancy detention camp on August 29, 1942 and deported to Auschwitz in convoy #12. He was murdered in Auschwitz. A certificate of his death was given to his wife on October 24, 1944. In 2022, the town of Bobigny (about 6 miles from the center of Paris) held a memorial service in memory of all those who were rounded up by the French police, held at the Drancy detention camp and shipped east to be gassed in Auschwitz. Their research team found me all the way in America as the next of kin to Herich Simenhaus. By this time, I have already uncovered the puzzle of “Dovid”.

After WWI, in nearly every city and town with a Jewish population, a Kehilla organization was established to offer social and religious support to the poorest in the community. Every Saturday, after Sabbath services concluded at the synagogue, volunteers went from courtyard to courtyard with large baskets, collecting donations to feed the sick in the Jewish hospital. People gave them whatever they could spare. When a doctor was called to a poor home, he often refused to accept money. The neighborhood doctor came whenever he was needed - day or night, rain or shine and he always wore a suit. Nearly everyone was weakened from the deprivation suffered during the WWI. A shortage of food, coupled with crowded living conditions with the windows tightly closed in the winter, contributed to the tuberculosis epidemic. This rampant disease was ravaging Poland, devastating and claiming entire families. There was no treatment - prevention was the only option.

Roman Emperor Constantine embraced Christianity in 300 CE. Until this time, from the 1st through the 4th century CE, Christians were persecuted. The early Christians were like Jews; in fact, they were Jews. They observed Shabbat, Passover and all the Jewish festivals. Constantine merged Paganism with Christianity. The observance of Shabbat was replaced with Sunday, Passover with Easter. The distancing between Christianity from Judaism started officially in the 4th century.

The typical work week in Poland was six days for Jews and Gentiles. The Poles, like the Jews, were strict in their Sabbath observance. However, the Jewish Sabbath is observed on Saturday, while the Polish Sabbath on Sunday. According to the Polish law everything had to be closed on Sunday, a Jewish work day. Since the Jewish economy would have a difficult time surviving on a five-day workweek, most Jews secretly worked on the Polish Sabbath.

By law, stores in Poland had to close at seven in the evening, but every store had a back door. This allowed many stores to stay open longer for people who needed to shop after work. The police knew about this and often enforced the law by giving summons to the shop owners. A small bribe usually kept the police away for a few weeks. The sanitation inspectors paid visits as well. There were high penalties if things were not clean and orderly. With overcrowded conditions, it was difficult to pass these inspections. The Jewish apartment and business owners in my mother’s neighborhood often endured insults of the sanitation inspectors. Even as a little girl, my mother understood that one penalty for the offenses was to hear the official’s sneer: "Jews, go to Palestine."

A beautiful, modern elementary school was completed right in my mother’s neighborhood in 1925. It had playgrounds on each side of the building, newly planted trees and flowers, a bathhouse for the students, and a small house for a caretaker. To my mother, this looked like a picture straight out of a fairy tale. She made up her mind that she would be admitted to that school at the beginning of the school year. My mother registered for the 2nd grade, to this brand new public school, by climbing through an open window. She and my grandmother had been waiting in the line for over two hours when something happened that to my mother was a miracle. She saw a window of the registration room open wide. She didn't hesitate. She climbed through the low window and took her place in front of the big desk.

The first day of school, September 1, 1925, was one of the happiest days of my mother’s childhood. She walked proudly with all the other children from her street, wearing the same uniform as the other girls—a navy blue dress with a white collar. The boys, in their dark slacks and white shirts, looked handsome. At school, my mother's young mind was impressed with patriotic spirit. After 123 years of occupation and division by Russia, Prussia, and Austro-Hungarian Empire after WWI, Poland became a deeply patriotic country. Studying, memorizing, and reciting the works of the great, patriotic Polish writers who wrote throughout those years, was an important part of school’s curriculum.

During the summer break, wealthy children went with their families to the well-known summer towns and health spas outside Warsaw of Falenica and Otwock. They came back suntanned and rested. As my mother’s family could not afford such things, she stayed home and played with the other children on the street or in the courtyard. They entertained themselves by playing with a ball or by jumping hopscotch. My mother lived every day with the anticipation of being back in school in September. She always remembered her school days with emotion. She had always been eager to learn and felt lucky to have been accepted to the second grade in a time when so many school children were still receiving no education. School became the place where she could forget the hardship and poverty at home.

As years after WWI passed, my mother’s family finally relaxed and allowed themselves to think the sun was shining for them too. Even if they still lived in that small gray room on the fourth floor. The sunshine entered their lives in spirit, they permitted themselves to believe in a brighter future. On Fridays, my mother loved going with her mother to shop in the open market where food was fresh and less expensive. Farmers from surrounding villages arrived in the streets of Warsaw with fresh milk, eggs, chickens and fresh produce. This makeshift market was the least expensive way for people to buy food. The milk had to be boiled since many cows were sick with tuberculosis. On Fridays the market was always crowded, dusty and loud, packed with people shopping for Sabbath. My mother was amazed by the wide array of harvest. The farm animals made noises and people bargained loudly. She stayed close to her mother; it was easy to get separated from her among the stands, goods, and the crowds of people shopping.

One Friday in 1927, grandmother’s face was pale and drawn as she waited for my mother to finish her afternoon snack of tea with a slice of bread and butter. My mother was trying to share about her teacher, how she made an example of her homework in Polish class again, but her mother just nodded absent-mindedly. That Friday, her mother did not rush from stall to stall, grabbing the vegetables and smelling the fresh produce, as she usually did. She walked slowly, haphazardly putting things in their baskets and showing little interest in the purchases. As soon as they got home, her mother lay down in her bed and fell asleep. At sun-down, the beginning of Sabbath, the siblings lit candles and prepared a meal as best as they could. The next morning, their mother awoke to find that her left hand and leg were paralyzed. The doctor explained that a vein had burst in their mother's brain and that she suffered a stroke. They heard the awful words: "There is nothing I can do for your mother." She was unconscious when the ambulance arrived to take her to the Jewish Hospital at Czyste in Warsaw. Overnight my mother and her siblings stopped smiling, most of the time they sat in a corner of their small room with their heads down. Within two weeks of her mother's stroke, they had become disheveled-looking and gaunt, eating only bread with tea. They all hoped that mother's health would improve, they waited for a miracle. But their mother’s condition only worsened. My mother no longer had a mother - she was ten years old. The siblings brought their mother home from the hospital. After school, my mother would sit with her mother on her bed, kiss her, and beg her to talk, but she did not answer. The siblings plunged into poverty taking care of their mother at home for the next four years.

The economic disaster of the 1930s was especially severe on an agricultural country like Poland. The start of the Great Depression brought with it tension between the working class and capitalists, and at the same time, the relationship between Polish nationals and Jews deteriorated rapidly. After the death of my grandmother in 1931, my mother’s siblings started the rebuilding of their lives. Three of them marry, pull themselves out of poverty and have children. All this while Poland plunged deeper into the Economic Depression and with Piłsudski’s death in 1935 Antisemitism came out into the open through Roman Dmowski’s Endecja party.

After the war, under communism, Antisemitism never went away as it was supposed to. My first memory, of my first day of school is very different from my mother’s. I was seven years old when I learned that being Jewish meant I was different from my Polish schoolmates. September 1, began with so much anticipation. I have been looking forward to this day for four years, since the day my older sister first started going to school.

On my very first day, I was taunted by classmates before I ever entered the building.

"You are Jewish, Poland is not your country, Palestine is where you belong."

I didn't understand. This was the first time I'd heard that my home was in Palestine. It also was the first time I wondered whether being both Jewish and Polish was actually possible. I could not wait for the day to be over and to run home. The day became a blur and what I remember clearly is that I was already crying as I opened the door to our kitchen.

My mother sat with me and patiently explained what it meant to be Jewish. I can still remember the sadness in her voice and the tears in her eyes. My mother's reaction was eclipsed by my amazement. Our true homeland, she told me, was in Palestine. My response was a simple one: "Let's go to where we belong."

Stalin’s antisemitism came out after WWII. Nazism and later Stalin’s NKVD supplied Eastern Bloc countries and Arab world with the old Tsarist Antisemitic Propaganda to spread Antisemitism and anti-Western hate. In 1948 there were 14 Arab countries, with massive territories. Six attacked Israel: Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia. Stalin supported Israel at the beginning. Russia, via Czechoslovakia, was the only country that sold the old German war equipment to Israel when no one else did. Stalin wanted access to the Middle East. He believed Israel was committed to become a socialist country. Israel aligned herself with democracy and the west instead. Stalin’s influences in the Middle East evaporated and he became openly Antisemitic. The words Jews and Zionists became interchangeable. He called Zionism a racist system, singled out only one country, Israel, against having the right to self-determination. Jews were no longer safe in Soviet Russia. The murder of 13 Russian Jewish Poets in 1952 was followed by the murder of Russian Jewish doctors in 1953. Stalin died before they were executed in the Lubyanka prison. Stalin’s NKVD became the KGB after his death. The KGB supplied the Arab world with the fake Protocols of the Elders of Zion in order to spread anti-Semitic and anti-Western hate and to generate a widespread Muslim revolt.

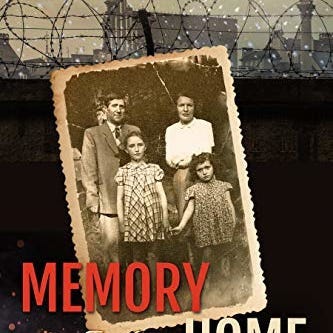

My book, Memory is Our Home, was published in English in 2015, in Polish in Poland in 2016. The second edition was published in 2020. It is available on: https://www.amazon.com/s?k=memory+is+our+home&i=stripbooks&crid=3600TCBN82YJY&sprefix=memory+is+%2Cstripbooks%2C91&ref=nb_sb_ss_ts-doa-p_1_10

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/memory-is-our-home-suzanna-eibuszyc/1120751675?ean=9783838214825

http://memoryisourhome.com/